1. Black box finance. In our latest letter, we described how financials led the market for the first quarter and yet, we reminded clients that we don’t own any depository financials. We wrote:

“As we hinted in our first page introduction, we are not particularly bullish on depository financials (i.e. banks). The community banks have too much capacity, significantly limiting growth. The large ‘money-center’ banks are subject to vast new legislation by the name of Dodd-Frank that we believe will significantly reduce their returns relative to historical trends. In addition, the big banks are essentially black boxes. They may trade below stated book value, but does anyone, including the CEOs and CFOs of these immensely complex institutions with their myriad derivative positions, really know what book value is?”

If yesterday’s revelation by JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon regarding unforeseen trading losses in their risk management group is not enough empirical evidence to close the case on our point, we don’t know what is.

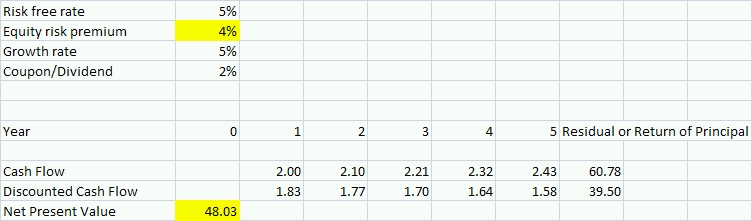

With highly levered banks, the black box could include positions that completely wipe out equity holders. This thinking on “money-center” banks is not new – we’ve continually emphasized it in both written and oral communications with clients for several years. All investors need to cope with uncertainty but our primary objective is to protect capital, so if there is a meaningful possibility of total loss we will pass. This framework is a hallmark of our investment process. We participate when the range of possible outcomes are all positive, or (for very small positions) when the probability weighted expected outcome is very high. Potential returns between 6% and 12% (see Excelon), are acceptable. Potentially being wiped out is not.

2. Jamie Dimon. Jamie Dimon remains an impressive leader. Frank, tough, and seemingly fair, he has built a career and a bank by methodically putting one foot in front of the other, taking the long view, and (for the most part) acting conservatively. There is a positive potential outcome of this event. If this causes Mr. Dimon to recognize the vast gulf between a 2 trillion dollar bank’s operations and his ability to monitor and control these operations, this event will guide the direction he takes the bank. JPMorgan would become a better institution. In addition, there is some chance that his approach to this issue will further enhance his stature as a banker and a leader. His frank mea culpa yesterday was a start in this direction.

3. Ben Bernanke. The primary culprit here does not receive a JPMorgan paycheck nor work in Manhattan (or London). Rather, his check is signed by Uncle Sam and his office is at 20th & Constitution Avenue in Washington, DC. While it is still unclear exactly what positions JPMorgan held and holds in its CIO office, financial repression a la Ben Bernanke is likely the root cause of JPMorgan’s current mess. The “London Whale’s” trading activity was just a natural reaction by a profit seeking financial institution to zero interest rates. Bernanke dangled the bait and the whale took it. The Federal Reserve has stated that a primary goal of their financial repression is for investors to “step out on the risk curve” (i.e. microscopic Treasury bill yields force investors to take risk to increase their yield; moving to longer durations, corporate credits, equity, leveraged derivatives, etc.). Like all central planners before them, this Federal Reserve ignores the law of unintended consequences at citizens’ peril.

The information contained herein should not be construed as personalized investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. There is no guarantee that the views and opinions expressed in this blog will come to pass. Investing in the stock market involves the potential for gains and the risk of losses and may not be suitable for all investors. Information presented herein is subject to change without notice and should not be considered as a solicitation to buy or sell any security.